September–October 2021

Reel Education

In the classroom and on the water, these high school students learn fishing skills and conservation

Tom Hazelton

Justice Rebrovich has been working his 16-foot fishing boat along the shoreline for almost two hours when he finally gets a hit. Rebrovich, a junior at Nashwauk-Keewatin High School, leans back and sets the hook. The fish swirls aggressively in the lily pads as it tries to shake the hollow-bodied frog lure.

“About time, baby!” he says, reeling hard. Soon, a largemouth bass is boatside and in the landing net.

“Yeah, honestly,” says his fellow student and angling partner, Daniel Clusiau, laughing, as he hands the net to Rebrovich.

It’s sunny and breezy—a nice May morning for the final 2021 outing of Spartan Angling, Nashwauk-Keewatin’s elective fishing class. Today, Spartan Angling is out on Bray Lake, just north of Nashwauk, a small lake rimmed by forest, with cabins tucked into the trees. The whole class is fishing—a few in another student’s boat, a couple in a paddleboat, and the rest on math teacher Luke Adam’s pontoon.

Adam created the for-credit class, first offered in the spring of 2019, to give students in grades 9 through 12 the chance to learn or expand on their fishing skills and to introduce them to fish biology and conservation concepts. Lessons include basics like tackle and rigging and deep dives into fish species and conservation. They also have several fishing outings each semester, both on the ice and on open water, some as weekend trips and others as school-day field trips. Adam says that while several schools around Minnesota have fishing teams, most are extracurricular and often oriented toward competitive fishing. He doesn’t know of any other schools offering a for-credit class focused on basic fishing skills and conservation.

“We’re teaching kids a lifelong skill,” he says. “You might play football until you’re 18, but you can fish your whole life.”

Both Clusiau, a sophomore, and Rebrovich signed up for the class mainly because it sounded fun, but they found it to be more interesting and educational than they’d expected.

“It even teaches me a lot of stuff,” Rebrovich says. “Like invasive species … or the history of Red Lake, and how overfishing really messed it up and it’s in, like, recovery right now.”

He thinks that the class is great not just for kids like him, who have an angling background, but for those who didn’t grow up on the water.

“I’ve fished my whole life,” he says, making another cast with his baitcaster, using his thumb to brake the spool and dropping his bait right on target next to the bank. “A lot of kids don’t get that chance.”

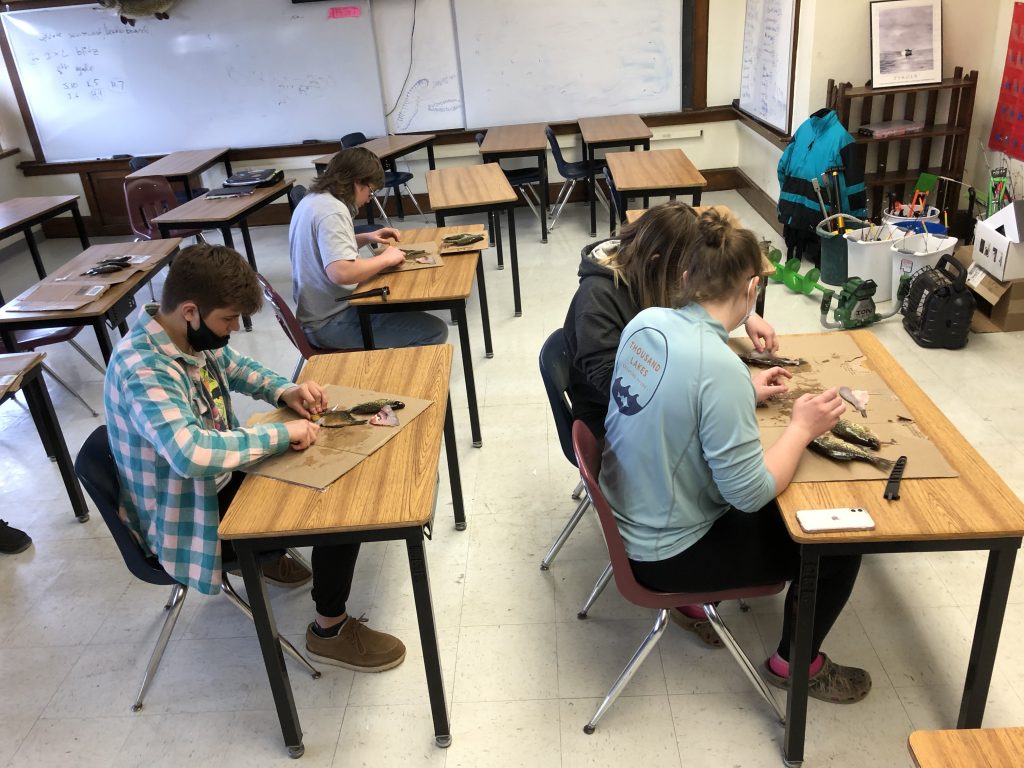

The previous afternoon, Adam teaches the kids to tie spinner rigs in his math-slash-fishing classroom at the high school in Nashwauk. A dozen students, a mix of girls and boys, make up the class, which, during the height of the COVID-19 pandemic, had to be adapted for online learning. Back in the classroom, the kids are engaged, but with a relaxed, end-of-the-year vibe. They pass around spinner-making materials: hooks, fluorocarbon leader, beads, and spinner blades.

Adam gently steers the room. The first step: tying the hook to the line.

“We’re gonna use the clinch knot,” he says. “Remember the twisty one?”

Some of the students deftly knot their hooks in place with well-practiced turns. Some lean forward to better see Adam’s demonstration.

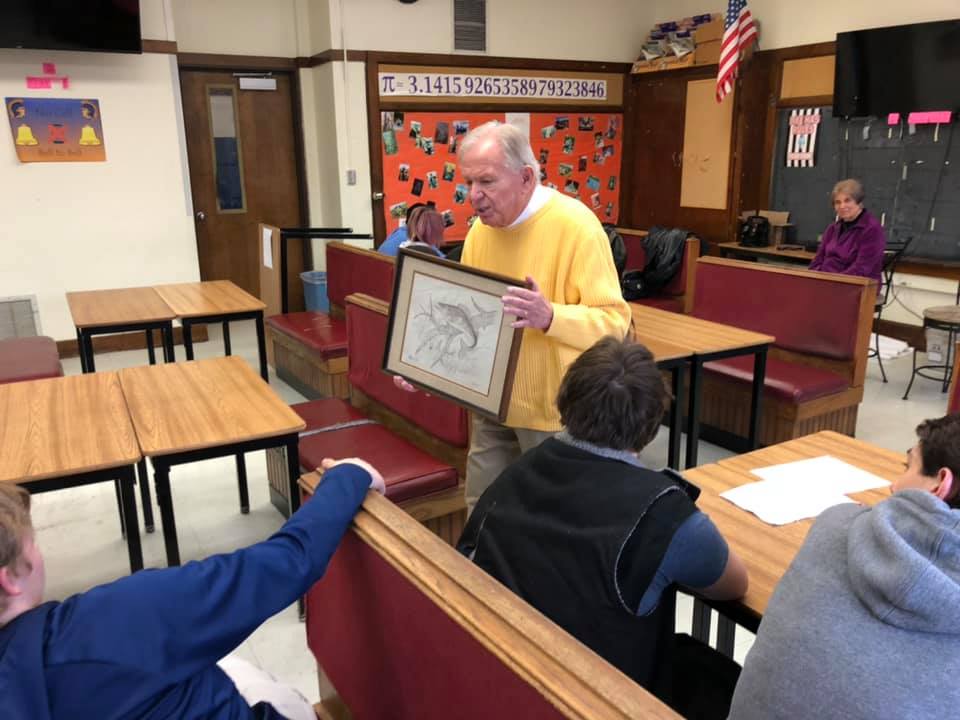

The classroom has a fishy feel amid the math trappings. The white board, still marked up with a few final algebraic formulas, is crowned by a large mounted northern pike with a blue surgical mask over its toothy face. Beneath a 20-digit printout of the number pi is the NKHS Fish Game Outdoor Wall, where students and staff pin photos of their outdoor pursuits.

After the spinner rig demonstration, Adam points, with the tip of a fishing rod, to a depth map of Bray Lake, where the class will fish the next morning. He quizzes students on which areas of the lake look best for finding different species of fish, and shares information on where he’s caught fish before and what kind of bait and lures work best.

Adam has had a cabin on Bray Lake since the early 1980s, so he really knows the lake. Many anglers keep such knowledge close to the vest, but Adam is happy to share his wisdom with a room full of people.

“I just want the kids to be successful. To have a good time,” he says after class, adding that not all the students have had the same outdoor opportunities he grew up with.

Adam believes that Spartan Angling gives students a chance to connect to the outdoors.

“Fishing doesn’t care about socioeconomic status, or race, or physical ability,” he says. “You don’t have to be an elite athlete to fish.”

And in Adam’s class, you don’t necessarily need your own equipment, either. Piled in a corner is a jumble of fishing rods and tackle boxes available for the students to use if they don’t have their own.

Much of it was purchased with funds from the Minnesota Department of Natural Resources’ Angler and Hunter Recruitment and Retention Grant program, which aims to help local groups interest Minnesotans in the outdoors. The grant also helps pay for things like resort fees, boat rentals, and bus charters for class trips, such as a recent outing to Lake of the Woods.

Jeff Ledermann, DNR Fish and Wildlife education and skills team supervisor, worked with Adam on the grant process. Getting kids involved in the outdoors is critical, he says during a phone call a couple of weeks later, and not just for their own enjoyment. It’s important for the future of fishing and conservation in the state.

“We know that people who are connected to nature, and spend time outdoors, are more likely to act in ways to protect it,” Ledermann says.

The tricky part is working outdoors activities into the curriculum. “You can learn a lot about math and science … by participating in archery or in fishing,” he adds. “It’s getting teachers to look outside the box, frankly. Luke [Adam] has done that.”

In addition to two DNR outreach grants, Adam has found strong support from local service organizations and businesses that have donated or discounted gear for the class. “Fishing seems to be universally supported, especially when you can tie kids into it,” he says. “You don’t really need to candy coat it.”

After the outing on Bray Lake, Adam and his class gather at his cabin. Venison brats sizzle on the grill while Adam and his students discuss how the buffer of brush and tall grass between his mowed lawn and the lake helps protect the water from erosion and pollution. They also drag a seine net along the bank to see what kind of fish are using the near-shore habitat.

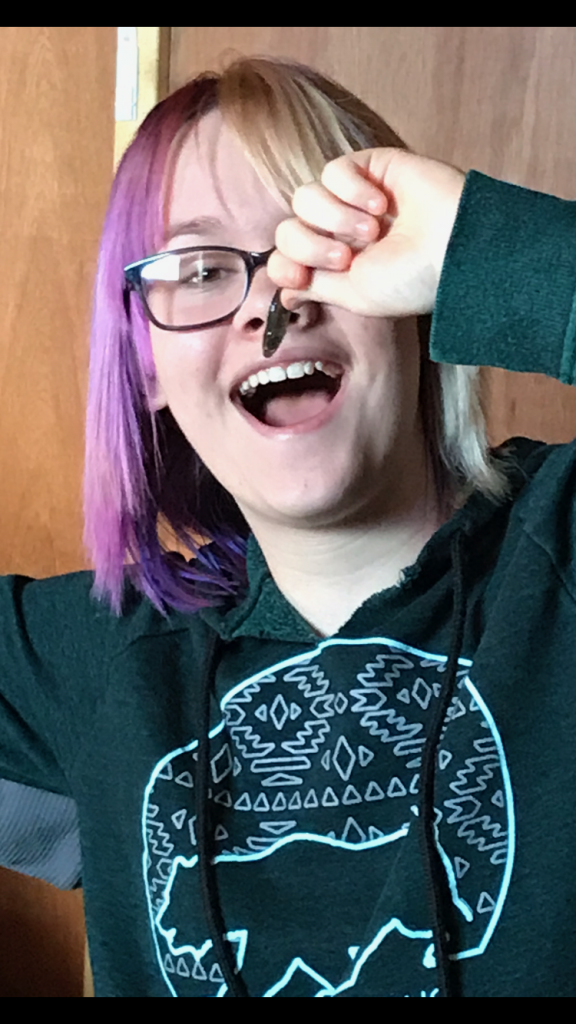

Later, Kaydince Thoennes, a junior, stands at a picnic table where a half-dozen northern pike, caught that morning, await the knife. The fillets will be added to walleyes the students caught on Lake of the Woods, then shared in an end-of-the-year fish fry at the school. “I think it’s cool,” Thoennes says when asked why she wanted to clean the fish. “And I think I’m good at it.”

Thoennes learned to fish as a young kid, but says her family had gotten away from it in recent years. She originally signed up for Spartan Angling because she needed to take an elective class. “I thought it was gonna be boring,” she explains, removing the thin strip of meat that contains the northern’s pesky Y-bones. “But I actually turned out to really like it.” Especially, she says, since there were other girls in the class—four this semester.

With the first northern filleted, Thoennes asks Adam if they can check the predator fish’s stomach to see what it had been eating.

“We’ll do a little lesson here,” Adam says, and students gather around. “What do you think is in there?”

“A minnow!” comes the chorus reply.

Adam cuts a small incision in the end of the pike’s stomach and squeezes from the bottom, like it’s a slimy tube of toothpaste. A small half-digested fish with faint vertical stripes slides out, to the loud disgust of a few students.

“Whoa! Perch!” says Thoennes, reaching for the knife. “Can I do some more, Mr. Adam?”